How U.S. Hospitals Pay Nurses and Why It’s an Issue

Nearly a third of Americans have not sought medical care just to avoid the cost. It’s no wonder why. It’s difficult to predict how much you will end up spending on a visit to the emergency room or even a trip to the doctor’s office. Prices vary significantly depending on where you live, what services you receive, and what kind of insurance you have.

One of the many culprits of this problem is our outdated “fee-for-service” (FFS) model that many healthcare centers in the U.S. still use.

In FFS systems, every service that a doctor orders (e.g., tests, scans, surgeries, and prescriptions) translates into a profit. So, the more doctors a facility has, the greater their profit opportunities. The result is higher-priced, lower-quality care.

But it’s not just patients who are exploited in these healthcare systems. Nurses are also taken advantage of.

Yet, because it’s more difficult to attach a monetary value to many of the services nurses provide, like educating patients and providing emotional support, hospitals categorize RNs as a cost instead of an asset.

“The problem is these facilities are all driven by a profit margin. That’s what they’re concerned about. To them up in the ivory towers, nurses are a labor expense,” Silver says.

The presence of capitalism in healthcare creates a conflict of interest that perpetuates artificially high costs for patients, low pay for healthcare workers, and problems staffing hospitals.

Though there have been efforts to steer hospitals toward new healthcare models, there hasn’t been a significant enough shift. The havoc that COVID-19 wreaked on our vulnerable healthcare system has highlighted its problems, which can hurt nurses and patients the most.

How FFS Systems Affect Nurses

In FFS systems, a hospital’s goal is the same as any other business: to maximize profits and reduce cost. But physicians and nurses are not categorized in the same way. Since doctors can write prescriptions and order procedures, they are seen as the cash cows.

Nurses, however, are seen as more of a line item in a budget rather than a way for organizations to generate income, explains Kara Yates, an RN and cochair of the Washington State Nurses Association (WSNA) at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

The association recently reached a tentative agreement with the hospital after 900 nurses took part in a picket and months of bargaining.

In for-profit models, hospitals err on the side of understaffing nurses rather than risking spending any more money than necessary — even at the expense of nurses’ well-being and patient safety. The minimum recommended nurse-to-patient ratio is 1:3 in teaching hospitals and 1:5 in general hospitals. Yet, many facilities overburden nurses with more patients than they can handle because they know nurses will step up to the plate.

Unlike an office job, in healthcare you can’t extend a deadline or push unfinished work off until the next day. Each inpatient must be checked on and treated multiple times throughout a shift. So nurses are constantly pressed for time, rushing from patient to patient, and skipping their breaks. The result is compromised care and burned out nurses.

Nurse burnout is not equivalent to occasional work-related stress. It is caused by an unsustainable level of pressure that results in cognitive and emotional symptoms. When sustained long term, it can lead to physical consequences, such as musculoskeletal disorders, heart problems, metabolic disorders, and various mental health conditions.

Burnout is not unique to the pandemic; it’s a pre-existing situation that has been exacerbated.

Right now, hospitals around the country are scrambling to hire nurses to avoid having to pay premium rates for travel nurses. But once COVID is no longer causing rapid fluctuations in hospitalization rates, the incentive to understaff hospitals will still exist unless systemic changes are made.

How FFS Systems Affect Patients

It’s obvious that profit-centric healthcare systems lead to high prices for patients. But a high hospital bill may be the least of your worries as a healthcare consumer.

Despite the fact that the U.S. spends much more on healthcare as a share of our gross domestic product than other wealthy countries like Germany and the United Kingdom, it scores worse in health outcomes than many European countries.

“If you shortchange the process and you overwork these nurses at the same time … what do you think the outcome’s going to be?” Silver says.

In the worst cases, a short-staffed hospital leads to preventable deaths. A 2020 study from University of Pennsylvania found that patients in hospitals with higher nurse burnout scores were associated with a higher likelihood of in-hospital mortality.

The highly publicized case of RaDonda Vaught, a nurse who was tried for criminally negligent homicide for accidentally injecting a patient with the wrong medication, sparked more conversations around the connection between burnout and patient deaths.

But medical error is just one piece of the puzzle when it comes to FFS systems’ negative effects on patients. Outside of these rare instances, like a medical error, more commonly patients’ health is compromised when more profitable methods of care are preferred.

This happens when a physician is encouraged — implicitly or explicitly — to recommend surgical solutions over alternative treatments that may be just as beneficial, less risky, and less costly. Why? Because surgery is much more profitable.

Physicians acknowledge that this is happening. In a 2017 survey of more than 2,000 U.S. physicians, the average respondent agreed that 20% of medical care is unnecessary. About seven out of 10 said they believed that their peers are “more likely to perform unnecessary procedures when they profit from them.”

This pattern can also be seen among patients with chronic health problems and diseases. For example, a doctor may be more likely to prescribe cardiovascular drugs to a patient with early signs of heart disease than to push them to make lifestyle changes.

As Yates explains, “It’s much cheaper to get preventative care than it is to get treatment for a disease once it’s developed or to get care at an urgent care facility than at an emergency department.”

But often patients are pushed toward more expensive options later because they didn’t receive the correct preventative care earlier.

How does this play out in the real world? A 2019 study that compared the health outcomes of people with meniscal and osteoarthritis tears provides an example. The study separated subjects into two groups: those who received surgery as treatment versus those who opted for physical therapy (PT).

Researchers found that there was no significant difference in the health outcomes or pain levels between the two groups after patients had recovered. In other words, both methods of care were effective.

Surgery is more expensive and riskier than PT. It costs between $5,000 and $10,000 or higher (compared to about $100 per PT session). It also can take months to recover from, during which time, the patient may not be able to work. Additionally, joint surgery increases the chances that replacement will eventually be needed.

This is not to suggest that doctors seek to endanger or extort patients. Doctors can’t force patients to make healthy lifestyle changes or detect health problems before warning signs appear. But in a system where health outcomes typically come second to profit, the burden is placed on the patients to seek care to avoid preventable health problems.

How FFS Systems Affect Hospitals

Ironically for FFS hospitals, understaffing their units has cost them significantly. In recent years, thousands of healthcare workers have left their jobs due to unreasonable expectations and unsafe working conditions, which were worsened by the pandemic.

The average cost of turnover for a bedside nurse is currently about $46,000, according to a survey from Nursing Solutions Inc. Last year, the average hospital lost between $5 million to $9 million due to turnover alone, and the situation is poised to get worse. A third of nurses plan to leave the profession by the end of 2022, almost half of them citing burnout as the primary reason.

Now that maintaining nursing staff is affecting healthcare employers’ bottom lines, hospitals are joining the conversation. In 2022, the American Hospital Association (AHA) declared workforce challenges a national emergency in a document requesting federal funding.

It points to COVID-19 as a major culprit for staffing struggles. It also highlights that hospitals’ labor costs have increased due to the scarcity of local RNs willing to work and the necessity of employing travel nurses.

While hospitals can’t be blamed for the chaos that played out in intensive care units during the onset of COVID-19, their reluctance to listen to healthcare workers earlier played a part. Nurses have been speaking about understaffing for decades. Many healthcare centers were wearing their nurses thin for years prior, creating a shaky foundation for a pandemic.

While associations like the AHA blame their staffing issues on a “shortage of workers,” this isn’t entirely true. There are many licensed RNs in the U.S. who are not working in the field because they are unwilling to work in understaffed facilities.

“If you want to bring in and keep the best nurses, know that nurses are the best PR for that facility,” says Edna Cortez, another cochair of the WSNA and RN at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

And if a hospital becomes known for poor working conditions, recruiting becomes increasingly difficult; turnover turns into a vicious circle.

Many U.S. hospitals have been operating in the red over the last two years, funneling COVID relief money into paying for travel nurses instead of fixing flawed institutional policies. This quick-fix solution has kept them running, but it won’t help them course correct, as nurse workplace issues will not evaporate with the pandemic.

The Move to Value-Based Care

Healthcare workers, healthcare policy experts, and politicians have been pushing hospitals to replace or revise their FFS systems for decades. They are advocating for new “value-based” models that center patients’ health outcomes instead of profits to fix the system at its roots.

In 2010, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) included a few soft initiatives that aimed to incentivize healthcare employers to use other types of care models. But in 2019, almost a decade after the ACA was signed into law, only about 38% of healthcare spending was conducted through a non-FFS payment model.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is pursuing value-based care. In recent years, CMS established a link between patient satisfaction scores and reimbursement rates to encourage hospitals to provide higher quality care. The higher the scores, the higher the reimbursement rates.

But when a hospital receives negative scores, and therefore lower reimbursement rates, this lowers hospital profits and unintentionally incentivizes them to cut costs like staff even more, making the core issues related to FFS systems worse.

Proposed changes to its reimbursement policies may offer more incentives for providers to carry out alternative models. Of course, this only applies to doctors and patients affected by CMS. And incentives are not mandates.

“The transition to value-based care needs to recalibrate how healthcare is measured, payments are reimbursed. There is no simple solution and quick fix,” says Lin Zhan, Ph.D., dean of UCLA’s nursing school.

There are many types of value-based care models that have been proposed, e.g., the bundled payment model, pay-for-performance, and the public utility model. All of them seek to prioritize quality of care and equitable access over profits.

For example, pay-for-performance structures reward providers if they reduce costs. They also require them to achieve certain care quality targets to receive bonus payments.

Silver has long been advocating for a public utility model. In the U.S., services like sewage, water, electricity, and sanitation are all modeled in this format. By definition, public utilities exist to supply essential services to communities while controlling prices and regulating processes.

Right now, hospitals have the freedom to control how they operate. Most are still choosing to offer healthcare as a commodity rather than treating it as an essential service. It’s up to healthcare workers and regular citizens to inform the public, professional associations, and legislators about the problems that FFS systems can cause.

What seems like a simple pivot to quality care requires major changes on the part of healthcare providers, healthcare reimbursement systems, and challenges and difficulties amid COVID pandemic-causing budget limitations, Zhan explains.

“Optimistically,” she says, “the healthcare revolution is already here. It’s the continued shift from FFS models to a system of value-based care.”

Meet Our Contributors

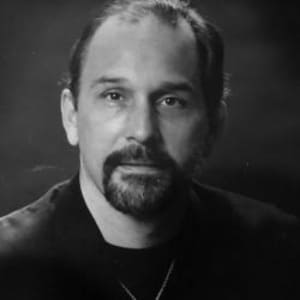

John Silver is an RN and healthcare policy expert based in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. He has been practicing since 1984, primarily in critical care. He later earned an MSN with a focus on health policy and ethics and a Ph.D. in comparative studies to search for solutions to problems within the U.S. healthcare system. He cofounded the advocacy group Nurses Transforming Healthcare with the vision of creating a patient-focused system with safe staffing levels. He speaks nationally and internationally about healthcare system restructuring and ethics in healthcare.

Edna Cortez is an RN at Seattle Children’s Hospital, where she has worked for more than 30 years. She also currently represents the Washington State Nurses Association as a cochair at her hospital. Over the years, she has worked in the medical surgical unit, the pediatric neonatal unit, and the cardiac ICU.

Kara Yates has been an RN at Seattle Children’s Hospital for 12 years and is also a cochair of the Washington State Nurses Association at the hospital. She works as a pediatric-certified charge nurse caring for patients in the pulmonary and craniofacial unit. In 2022, she wrote an op-ed for the Seattle Times about nurses’ experiences during the pandemic.

Lin Zhan is the dean of UCLA School of Nursing, where she is also a professor. She has been in academia for more than 20 years. She used to direct the doctoral program in nursing and health promotion at the University of Massachusetts Lowell School of Health and Environment and worked as a professor at the University of Massachusetts Boston College of Nursing and Health Sciences. Zhan’s interests include developing better measures for health-related behaviors and promoting diversity in higher education diversity and workplaces.